Our research

The rapidly growing field of experimental philosophy uses empirical methods from the social sciences, and especially psychology, to address philosophical questions. Our interdisciplinary group has contributed to extending the field’s philosophical reach and methodological repertoire. We use methods from psycholinguistics, computational linguistics, social and developmental psychology, and neuroscience, and explore how to complement quantitative with qualitative methods. Our research is closely bound up with interests in philosophical methodology and classical philosophical concerns about language, perception, the mind, memory, knowledge, and morality. We study philosophical intuitions and arguments, and philosophically relevant cognition more generally. We explore new ways in which empirical findings can be brought to bear on philosophical questions and problems. Much of our research addresses four topics:

Experimental argument analysis: Reasoning with stereotypes

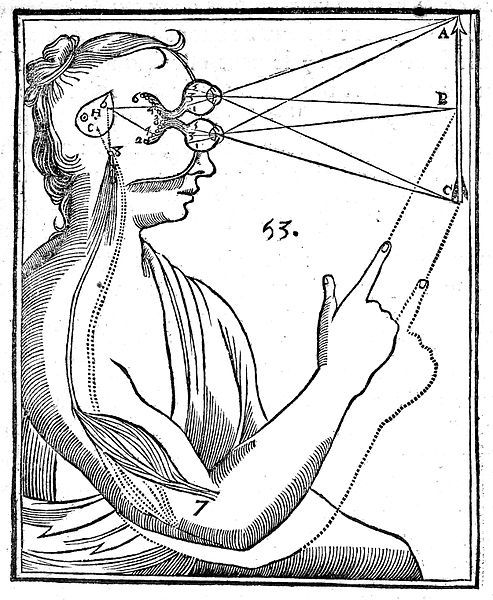

How does ordinary language shape thought? To what extent are we masters of our own thought? Can insights into automatic cognition help assess philosophical arguments? We address these questions with eye tracking and distributional semantic analysis. These methods provide a window into automatic language processing. We study how stereotypes, automatic language processes, and the biases that beset them, shape verbal reasoning. Transforming ideas from ‘critical’ ordinary language philosophy, we deploy findings to expose and explain fallacies in philosophical arguments and explore consequences for conceptual engineering. Related, in some ways underpinning, research seeks to extend and redefine current conceptions of semantic memory.

Fragmented beliefs: Rethinking rationality and ‘common sense’

Appeals to common sense are common in philosophy and public discourse. But is there even any such thing as ‘the’ common sense view? A radical new challenge to such appeals arises from psychological findings about ‘belief fragmentation’: Different cognitive processes generate conflicting beliefs; these are stored in different ‘belief fragments’ which are never systematically screened for coherence. We investigate belief fragmentation from a developmental perspective as well as from a philosophical perspective, as a challenge to traditional conceptions of rationality and to philosophical methodology, and as a source of characteristically philosophical problems.

Moral psychology

Our third research strand seeks to develop and test a model of the influences on moral judgements that helps to address several key issues in moral philosophy and moral psychology. This research sheds light on the reasons for apparently inconsistent and unjust judgements, and on how best to promote rational and fair moral decision making by, for example, jurors, managers, teachers, and parents.

Philosophical traditions and intellectual virtues

A grant from the John Templeton Foundation helps us develop a new line of research: The ‘ameliorative psychology of philosophy’ examines how doing philosophy can help people become better thinkers and persons. Our project empirically examines the effects of education in different philosophical traditions: analytic, Buddhist, Confucian, and Thomist philosophy. We examine how education in each tradition influences key intellectual virtues: wisdom, intellectual humility, curiosity, and reflectiveness. In collaboration with partners from the University of Pittsburgh, we address this question with a cross-cultural study involving Europe, North America, South Asia, and East Asia.

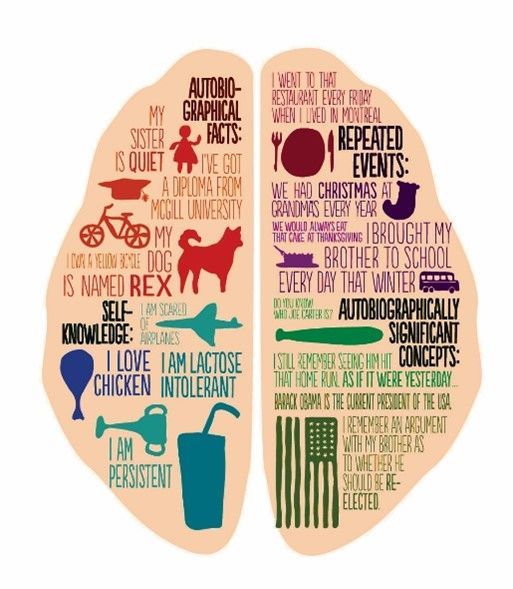

Personal semantics: the interface of memories

Does our experience colour how we understand language? How? At what level? The emerging field of personal semantics studies how our ability to remember past experiences (episodic memory) interacts with our ability to extract meaning from discourse and knowledge from the world around us (semantic memory). This interaction yields intermediate memory representations. Our research has developed new memory tests to study semantic and episodic details in parallel. We use methods and concepts from cognitive neuroscience to better understand the nature of the intermediate memory representations, and in particular whether they correspond to separate memory systems in the brain.